SELMA / AUSTIN; PRIMARY / FRACTURED POROSITY; OIL / GAS

The first commercial oil field discovered in Mississippi was Tinsley Field, discovered in 1939 when Union Producing completed the #1 Woodruff in a sandstone encountered in the upper Selma Chalk, later named the "Woodruff Sand". Tinsley Field went on to produce over 200,000,000 barrels of oil from the "Woodruff Sand" lenses deposited in the upper Selma, a series of calcareous sandstones that pinch out across the western half of the large Tinsley anticline. Across a broad syncline from Tinsley Field, Flora Field produced over 7,000,000 barrels of oil from a similar lens of sandstone - this time deposited at the very top of the Chalk. A few miles south of Flora, the Jackson Gas Field - discovered and developed during the Great Depression - produced over 150 BCF of gas before being converted to gas storage. The availability of cheap and plentiful natural gas during the crippling economic crisis of the 1930's enabled many schools, colleges and businesses in the Jackson area to heat their buildings and water at a very low cost, and survive the Depression. The producing reservoir at Jackson Gas Field is an intensely karsted Selma Chalk that yielded individual flow rates as high as 30,000,000 cubic feet of gas per day.

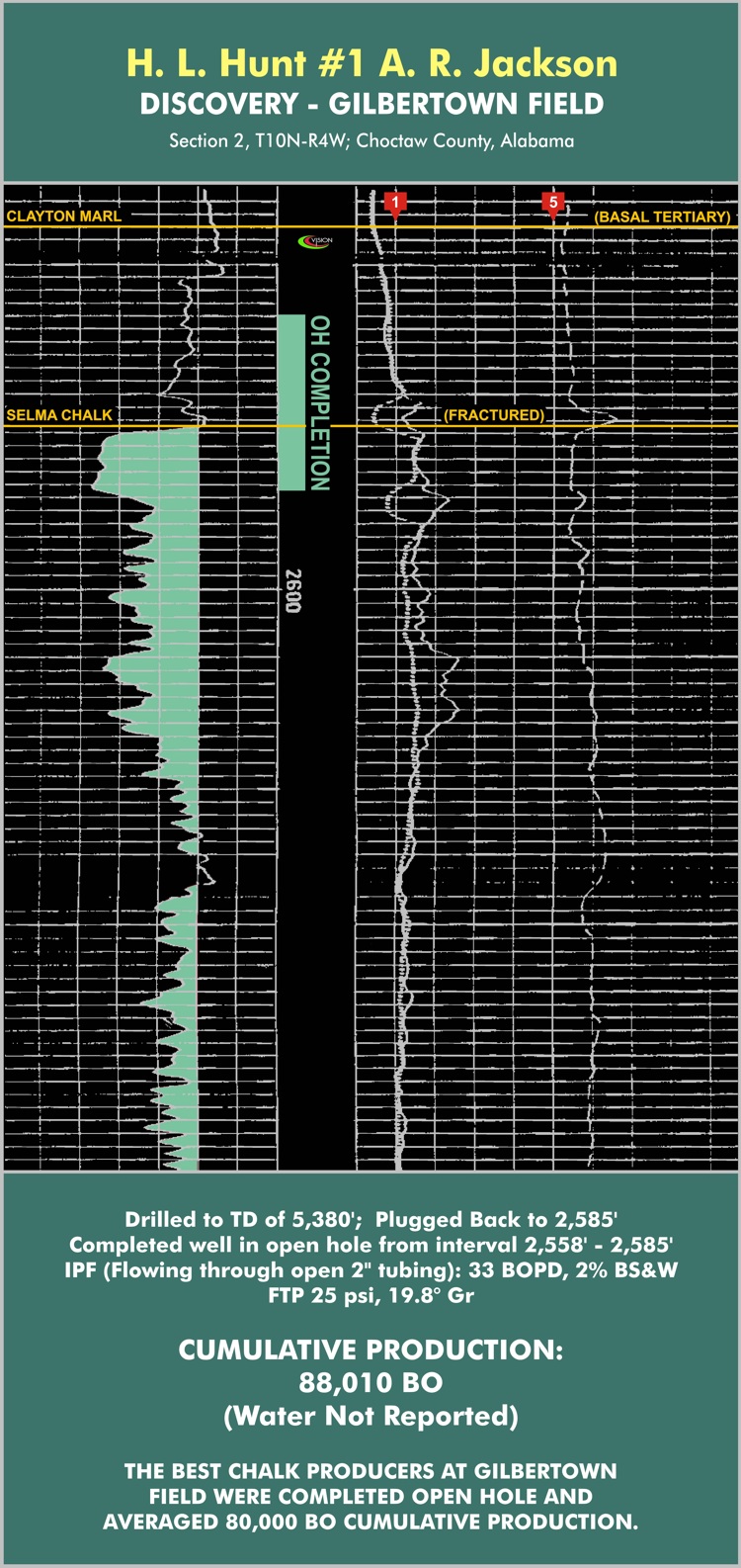

The first commercial oil field discovered in Alabama was Gilbertown Field, discovered in 1944 when Hunt plugged back an unsuccessful Lower Tuscaloosa test to complete the #1 A.R. Jackson as an open hole completion across the uppermost portion of the Selma Chalk. The Selma Chalk reservoir at Gilbertown Field is an extensive fracture system located on the downthrown side of a series of down-to-the-north faults that were first identified by surface mapping in the early 1940's. What the Hunt geologists did not realize in 1944 (and few geologists realize even today) is that NW-SE oriented wrench faulting - where it intersects with (and literally tears apart) the extensional east-west oriented normal faulting - plays a pivotal role in fracture enhancement at Gilbertown, and the discovery well was actually completed at a location that falls within one such an intensely brecciated "intersection". The average open hole Chalk completion at Gilbertown produced approximately 80,000 barrels. The annotated e-log for the discovery well, the Hunt #1 A.R. Jackson, is shown at the bottom of this page.

Thus the Upper Cretaceous Chalk has earned a special place in the early history of oil and gas exploration in Mississippi and Alabama. Other important Chalk fields (located in Mississippi) include Pickens and Junction City Fields (oil), and Heidelberg, Gwinville, Baxterville, Sharon and Maxie Fields (gas). While Pickens and Junction City Fields produce oil from downthrown fractured Chalk reservoirs that are similar to Gilbertown Field - a fracture mechanism present in all Chalk fields, to some extent - there is a zone of porosity in the upper Selma Chalk in south Mississippi that has produced over 92 BCF at Gwinville Field and 67 BCF at Baxterville Field, and minor volumes of gas elsewhere, such as Maxie Field. This porosity has been described as a "talus" or debris zone and appears allochemical in nature. While porosity can be moderately good, permeability is poor and most wells completed in the talus porosity require stimulation to achieve commercial rates. To view a log that illustrates this upper Chalk porosity, click here.

In the shallow fractured Chalk reservoirs of Mississippi and Alabama, many geologists mistakenly believe that the presence of high induction log resistivity in the Selma Chalk is an indicator of oil-filled fractures (i.e., the induction log is "seeing" the oil in the fractures). This is incorrect. High induction log resistivity in the shallow fractured Chalk reservoirs of Mississippi and Alabama is an indicator of a significant amount of calcite precipitated in and along the fracture walls. In many areas, calcite has completely sealed the fractures in the Chalk. In other areas, the fractures are still "open" but a considerable amount of calcite is present. Chalk fractures are principally vertical in orientation and quite narrow, and older induction logging tools were simply unable to discriminate between the narrow fractures filled with oil and the surrounding "country rock". Not surprisingly, therefore, many prolific shallow Chalk oil wells exhibit a practically normal, or only very slightly elevated, resistivity profile across the fractured Chalk. Thus exploring for oil-filled fractures in the Chalk by focusing on zones of abnormally high resistivity can be fraught with risk; noting the presence of oil shows on scout tickets and mudlogs is a much more effective method. Finally, in the area north of Tinsley Field, late Cretaceous vulcanism led to the introduction of thick tuffaceous flows into the Chalk interval, and atop the Monroe-Sharkey Platform, igneous dikes and sills; these igneous intrusive and extrusive rocks also present a high-resistivity log signature, and caution is advised for Chalk oil and gas exploration in that "frontier" area.

In extreme southwest Mississippi, the prospective Chalk interval is not the Upper Selma Chalk, but the Lower "Austin" Chalk equivalent. This 100' to 200' foot thick interval is highly resistive (often exceeding 200 ohm-meters) and is typically a very hard and brittle, gray micritic chalk that is very susceptible to fracturing. Regardless of whether or not fractures (and hydrocarbons) are present, the resistivity of this Lower Chalk interval is always high in the southwest Mississippi / east Louisiana area. Thus, as was the case with the shallow Upper Chalk fractured oil reservoirs of east Mississippi and west Alabama, high resistivity in this Lower Chalk facies is attributable to lithology, not a hydrocarbon response. Fracturing in this southwest Mississippi Trend (primarily Wilkinson County) is enhanced as the Chalk crosses the Lower Cretaceous Shelf Edge and other large structures, resulting in a change in dip slope that intensely fractures the brittle Lower "Chalk". A more silty and elastic Middle Chalk section, directly overlying the denser micritic facies, absorbs most of the fracture propagation and forms an effective topseal. Traps in this trend have exhibited both normal and geopressured reservoir characteristics. There has been little exploration activity in this Lower "Chalk" Trend in Mississippi, despite the success of the development of the same reservoir in the Masters Creek Field Complex in Louisiana, a little further downdip and west-southwest of the Wilkinson County area. To view a mudlog across a productive Lower Chalk interval from the southwest Mississippi area, click here.

Steve Walkinshaw, President, Vision Exploration

This entire site Copyright © 2017. All rights reserved.